The Creative Penn Podcast For Writers

Crafting Story Worlds, Creative Control, And Leveraging AI Tools With Dave Morris

Why is creative control and owning your intellectual property so important for a long-term author career? How can AI tools help you be more creative and amplify your curiosity? Dave Morris talks about his forty-year publishing career and why he's still pushing the boundaries of what he can create.

In the intro, Writing Storybundle; Finding your voice and creative confidence [Ask ALLi]; Does ChatGPT recommend your book? [Novel Marketing Podcast]; Google IO expansion of AI search [The Verge]; Sam Altman & Jony Ive IO [The Verge]; Claude 4; my AI-Assisted Artisan Author webinars.

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

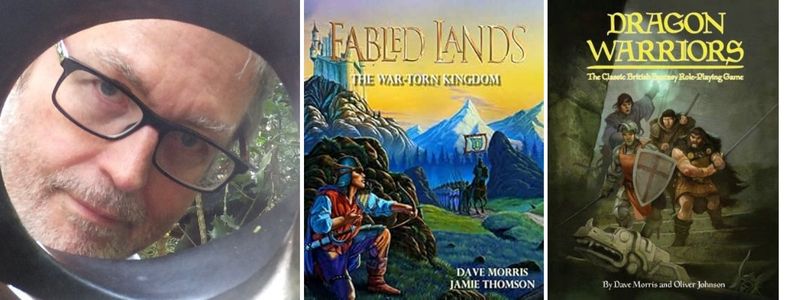

Dave Morris is an author and comic book writer, as well as a narrative and game designer, with more than 70 books and over 40 years in publishing. He is best known for interactive series such as Dragon Warriors and Fabled Lands.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Keeping your IP for long-term earnings

- Working on your own projects to maintain creative control

- Benefits of AI tools for long-series authors

- AI as a research and brainstorming assistant

- How creative confidence leads to confidence in using AI tools

- Using AI to advise on marketing strategies

- The potential of AI to enhance emotional expression in writing

- The future of gaming with AI integration

You can find Dave at FabledLands.blogspot.com, patreon.com/jewelspider, realdavemorris.substack.com or whispers-beyond.space

Transcript of Interview with Dave Morris

Joanna: Dave Morris is an author and comic book writer, as well as a narrative and game designer, with more than 70 books and over 40 years in publishing. He is best known for interactive series such as Dragon Warriors and Fabled Lands. So welcome to the show, Dave.

Dave: Hi, Jo.

Joanna: It's good to have you on. So first up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing originally, and how you've managed to stay in it for so long when so many have disappeared.

Dave: The introduction was making me feel exhausted, because, yes, it is 40 years. I think the Dragon Warriors is having its 40th anniversary this year. So 41 years I've been publishing.

At the start of the 80s, there was kind of a craze for role playing, and those kind of choose your own adventure books, solo role playing. So part of it is kind of a luck factor, but you have to look for those opportunities.

All publishers at the time needed people who could do that, and there weren't very many of us that could do words and equations and things, and I got lucky with that.

I think the why I've stayed in it is the early choices were whether to join the big series like Dungeons and Dragons, and Fighting Fantasy was a big one in Britain, or to do your own thing.

I went with smaller publishers and kept my own IP and kept control of it.

I think the difference there is, at first I thought, I wonder if this is a mistake. Like friends were making more and getting bigger checks than I was to start with, but then I noticed I was getting foreign rights checks a few years later that were really beginning to add up.

Of course, by keeping the IP, it means I'm still earning from those things 40 years on, because I still control them.

Joanna: That's really interesting. That decision, you said that was hard back then. Of course, we have seen in recent years, some of those comic book artists particularly are sort of trying to come back to the big companies saying, well, it's just not fair.

It seems a very strong decision to make back then, when being more independent was not really a thing.

Dave: Well, maybe I picked that up from comics because I was a huge Marvel comics fan. You know, I was 10, 11, 12, and I was aware of the problems of Jack Kirby, and even Stan Lee. I mean, he was paid well by Marvel, but considering that he's spawned a multi-billion dollar industry, he wasn't paid that much.

So maybe I just thought about creative control. I think partly it was just that I like to have creative control. You want to go in and be able to say the cover should look like this, and pick your own artists, and really just feel that it's your work, not somebody else's.

So although I have done plenty of hack work as well for other IPs, I think I bring my best game to my own stuff.

Joanna: Hack work. That's an interesting phrase. Is that writing for hire, really?

Dave: Yes. I mean, I did the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle books, for example.

Joanna: That's awesome!

Dave: I know, it is. I was a comics fan, so they said, “We want you to do these comics.” This was the kid’s department at what's now Penguin Random, or whatever the hell they're called.

I said, “You know, they're not kid’s comics. They're very dark, indie, underground comics.” And they said, “Oh no, they're doing a complete reboot.” I was amazed, because I only knew the very violent original version of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

I enjoyed writing them, and I later discovered I was the only author they trusted to come up with new stories, for some reason. So I ended up doing a bunch of new ones. Which, again, I think if they just said, “Take a TV episode and adapt it,” I wouldn't have been nearly as interested in doing that.

Although I did also do Thunderbirds and Stingray books, and that was mainly because I'd been such a huge fan of them when I was a kid that I would have done that for nothing. I didn't tell the publishers that.

Joanna: That's brilliant. How do you span all the genres and all the types of books?

Because you do game stuff, you do comics, you do book books. So how do you sort of see your projects, in terms of the work you choose to do?

Dave: That's a very good question. I actually didn't get into doing comics until about 10 or 12 years ago, and that was only after a games company I was working at had collapsed and a comic just came along. Random House was launching one, and they said, “Do you want to work on it?”

I actually discovered I really enjoyed writing comics, which shouldn't have been a surprise, but I don't know why I'd left it so long.

I think one of the things I probably bring is I always think that there's the element of writing, but because I'm a game designer as well —

There's an element to which —

I'm not just trying to create stories, but systems that create stories. I'm very interested in the world building and the means of having emergent narratives.

I saw an interview with Robert Harris, and he was talking about how he did all the research for his historical books, and he said 80% or 90% of it the reader never gets to see. Of course, if you're writing a game, all the law might eventually become relevant, so you kind of have to put all that attention in.

You can't just think, “Well, they won't go around the back of the houses, so I can have a flat piece of plywood there.” You have to allow for the possibility that the story could go anywhere. I think that's how I've come at stories, basically.

Joanna: I love that. Systems that create stories.

As you said that, I was thinking this is something that authors of series really need. I mean, like I'm looking at book 14 in my ARKANE series, and I have lots of ideas, but I feel like this system that can create stories.

Would you give some tips for people who want to write long series?

How would your lessons play into that?

Dave: Well, I think they're very lucky to be alive in the era of AI. I mean, I have that all the time. The VulcanVerse series, which I finished about a year ago, was three quarters of a million words long, and it was one of these choose your own adventure types.

Painting the continuity without AI—I mean, at that time, there wasn't a lot—but NotebookLM now would make that so much easier. Somebody asked me a question about the VulcanVerse books, where previously I would have had to go—

I got a French publisher said, “Is there a name for this mountain range?” I realized, looking for something that may not exist in the books, that's an open ended problem that could take all afternoon, right? But NotebookLM was able to tell me, “No, you never gave a name for those.”

When I presented it to ChatGPT, it said, “Would you like me to come up with some names based on the names in the area that you've already named?” So those things, I think they're really helpful because who wants to just wade through the text over and over again, looking for one specific detail of continuity?

It's like having a bible. Like if we do a game, we used to have to have the game bible, and for one massively multiplayer game, the bible was about 250 pages long. It had everything.

The physics of the world, the history of the world, the social cultures, how the language worked, how it's pronounced. Literally, everything that any designer on the team would need to access. Again, that now can just be put up effectively into an AI, and you can interrogate the AI for it. So those are very useful, I think.

Joanna: Well, then we'll get into it then because, of course, the other side of that you said, “We're lucky to be alive in an era of AI.”

I feel the same way, but some people would say, “Yes, but Dave, that means you don't have to write that anymore. Like, why do we need a Dave Morris when I can use ChatGPT to write a 250 page world bible?”

How are you dealing with AI, as someone who has a degree in physics and has been into this whole space for a while?

Dave: I mean, the physics course 40 years ago, or 45 years ago, had AI as a tiny module. Now, probably physics is a tiny module. In fact, Nobel Prize winners can be AI specialists who happen to win the physics prize.

I do hear a lot of people saying, “Oh, well, you're just saying the AI will do the writing, or the AI will do all the artwork.” Of course, they're really speaking, I think, from a position of not having tried it, because that's not how anybody really uses it.

You don't just leave it running, go and get a cup of tea, come back and the book is written. It's little things like the research that I was talking about. I had a little bit the other day where I needed to find a historical reference, and I thought it was in this book by Jean de Joinville, The Chronicles of the Crusades.

I was going through the book from my shelf, and it's a big book, and you gradually begin to think, did I imagine it? I mean, the last time I looked at the book was 30 years ago, so maybe I'm misremembering.

Then I thought, well, he wrote it in the 13th century, so I can find it on Gutenberg, put it into an AI, have it read the whole thing and tell me if I'm hallucinating or not. It found it, and I thought, right, that could have been an afternoon wasted for a tiny point that I needed before I could move on to the next part of the writing.

It's like an incredibly diligent, fast, patient, research assistant. A discussion brainstorming assistant. I can't imagine how I managed without it, really.

Joanna: It's funny you say that because I was talking to Jonathan, my husband, about this. I was like, this is one of those things a bit like Google. You know, when we all got Google, or the internet just in general.

Even my phone, you'll remember too when we had those Nokias, the little Nokias, and you're like, why would I ever need anything else? Like, I don't need that smartphone. What is this iPhone thing? Then, of course, that's all changed.

I did want to ask you then, because something I'm a little obsessed about at the moment is this idea of creative confidence. I hear you, and you and I both understand this, you said you don't just leave it running. You're driving it because you know you have taste.

You have your own taste, you have your own voice. You know what you like, you know things you're interested in. You can trust that.

What about people who are earlier on in their career? Maybe they're writing their first book, or maybe they're writing their first game, or whatever.

How can newer writers have creative confidence in working with AI tools?

Dave: That is tricky, of course, because we've effectively trained our brains, our neural nets in our heads, to already do that work. We can see which bits are the heavy lifting we want the AI to do. I think people will just learn different ways of working.

I mean, every generation has new technologies that come along. I'm sure when the quill pen came in, people were going, “Oh, people won't have the valuable time spent sharpening the quill pen, which is important thinking time.”

I don't doubt, if I went forward 50 years, I'd find the way people are writing is very different from the way I do it. I mean, they would probably think how antiquated that I talk about it as like a research assistant.

In 50 years’ time, you might have a neural interface anyway, so it might actually be directly wired into the brain. I was more keen on that before Elon Musk went crazy because now I don't want Neuralink anywhere near my brain.

Joanna: I'm sure there'll be other brands.

Dave: I hope so. Maybe if Google would do one, I'd probably end up with that one anyway.

I think, yes, the patterns that people use. I mean, you look at, say, people like Trollope and Dickens, and they were building these huge worlds. When you see their notes, you think, how the hell did they have two pages of notes for a book, that if you drop it, you'd break a toe.

How did they keep all that in their head? Especially Trollope, when he's only doing it before he goes to work every day. I guess they just train their memories really well.

One argument is we get lazier. That was the argument against writing when it was invented. People will forget how to remember stuff. They'll just write it down. Well, we've only got so much brain space. We don't need to clutter it with unnecessary tasks, I think.

I do think it's going to be interesting. I'm sure I will be constantly amazed to see how younger writers are actually starting to use it.

Joanna: Yes, it's interesting. I mean, I keep coming back to just curiosity and the tug that I feel towards things. So you mentioned a book written in, what did you say, the 13th century or something? I'm like, oh, I'm interested in that too because, you know, Crusaders and that kind of thing. Yes, I'm interested in that.

Like, you talk about role playing games, I am just not interested. Not my thing. So I think people, they just have to feel that tug towards whatever they're curious about, and then let that be the guide.

These tools can generate lots and lots and lots of ideas, hundreds and hundreds of ideas, and—

You have to say, “that's the one,” or “that's not the one,” perhaps.

Dave: Well, we've talked about, I'm now calling it Banjo Duel Days. It's like for the banjos in Deliverance, where they go so fast the strings break. I find the conversations where they exhaust me within minutes because it's throwing so much stuff at you.

I think a lot of it is keeping it on track because it always says things like, “Hey, do you want another example of X?” Like no, maybe let's not get into that because you'll pull me off course.

If I was going to be a devil's advocate about it, there is one thing about the old days where I'd find I needed to find something out, I'd get my nose in a book, and it might be an hour and a half later that I surfaced with the thing I wanted to find, but a bunch of other things I didn't know I wanted to find.

Now I can go straight to the thing and get on with the big picture, but there is that risk that you don't get that serendipitous discovery. I'm sure people will still read though. So it's just that what I don't want to do is end up researching for hours when I'm losing a bigger picture of the story.

I needed to find in one story a bunch of moral riddles. So not logic puzzles, but those kind of Porsches casket things that would have an emotional meaning, like Gawain and the Loathly Lady. It's a riddle, but it's more about feeling than fact, and it was for a medieval story.

So I asked Claude about it, and Claude goes straight to a bunch of 12th or 13th century medieval texts that I'd never heard of, and quickly found a whole bunch of these kinds of riddles. We could go through them, and 20 minutes later—it was only for almost a throw away scene—but it meant I had what I needed.

Otherwise I would have had to have gone into JSTOR and spent days looking for this stuff.

Joanna: Because we're interested in that, like we are interested in finding these things. I was writing earlier a freediving story, and I needed to get the exact type of fish that they would see at this particular dive spot in this particular place. It's very important to get the right thing.

I can use AI, but of course, there are hallucinations or whatever, which we like sometimes. I was like, no, I need to triple check this and everything. It's funny because we care about those, and—

Perhaps that's just part of it, the sort of trust that you will care about the things that are important to you.

Dave: You might afterwards. I mean, people might say, “Oh, well, you won't spend the time just accidentally coming across stuff,” but maybe you will. I mean, having been told about it by Claude, there's nothing to stop me when I finish my story for the day thinking, “Well, it's on Gutenberg. I'll go and have a look at all that stuff.”

So they're worried in some way that it will kill curiosity, but I always wonder what kind of mindset frets about that.

You and I are so excited by it, and we don't think it's going to stop us being curious. We don't think it'll stop us being creative. Some people fear that, and I wonder where they're coming from for that to be a fear.

Joanna: Well, like I said, I think maybe it's this creative confidence that you and I have you. I mean, you have a lot longer than me, but I feel like I just lean into it. Obviously, you've mainly been in traditional publishing, small publishers—

Are you coming up against the anti-AI stuff in the work that you do in publishing, or are you seeing widespread adoption?

Dave: Oh, you see a lot of opposition to it in role playing, and comics too. I mean, in the end, I couldn't continue my comic Mirabilis because it's a lot of artwork, and the artists have to work full time.

There was no way that the book advance would be able to pay them to work full time on 100 pages of comics. To pencil them, to ink them, to color them, we just couldn't have done that.

So I could now do that with AI, even if all we did was use the AI for the thumbnails, the layouts, which is quite a tradition in comics. The artist having got the basic composition of the shot, at least suggested to them, it saves 20% of the time. The coloring might be something, the inking, that the AI could do, but there's a lot of opposition.

Again, people say you're doing an artist out of a job, but I think, well, that's a case where the artist didn't get the job in the end because the economics of publishing just don't make it possible. Similarly, in a lot of small indie role playing publishing, they don't have a huge art budget.

Your choice would be no art or AI art.

I'm doing a Cthulhu app later in the year, and what we decided in the end was—because I did some AI art, and the guy who's doing the coding was saying, “Oh, I don't want any AI art.” So I sent him some stuff and he goes, “Oh, but that's absolutely perfect.”

Joanna: Oh, but that's good.

Dave: I said, yeah. I just know how to coax stuff out of this. So in the end, what we decided to do was we'd get the AI to do one set of artwork, we would also pay a human artist to do some very TRON-like artwork.

So basically the choice will be— because we'll probably do it on Kickstarter—is you can choose whether you want AI doing human-style art, or human doing AI-style art.

Joanna: Nice.

Dave: So no artist was done out of a job.

Joanna: Hmm, this is interesting. You mentioned the economics of publishing then, and you mentioned you published first in the 80s. I feel like a lot of the myths around publishing and money, like, “Oh, if I sell my novel, I'm going to make seven figures,” come from the 80s and 90s, when people did seem to get these big deals.

What else have you seen with the changes in the economics of publishing and being an author? How has that changed?

Dave: I was, as I say, lucky, because I was going into publishers who didn't know anything about game books and role playing and that kind of field. Consequently I could say, “Oh, this is the world I'm using, and I own it,” and I could get away with that. Whereas now they would try to own their own IP.

So if you're not a celebrity who's willing to do cozy murder, you know, if you just walk in off the street, you pretty much have to walk in with your IP already a bit established. So like The Expanse, or Hugh Howey with Wool Silo, as it is on TV, they'd already established there. Or The Martian, Andy Weir.

So they already established the IP, and then the publisher has to do a deal with them. If you walk in cold, you know, if I went back to being a 23 year old or whatever I was, walking into a publishing house now, they would be telling me, “We want you to use this IP, and we'll control it,” and they want to be able to fire you.

So you pretty much have to make sure you go in with cards in your hand, which will be an established audience of some kind.

Joanna: What are some of the other things that have changed in the industry that today's publishing myths are based upon?

Dave: If I went right back, publishing used to have very long lunches with lots of wine. It was very kind of genteel. You'd go into one of these old publishing houses, and a bottle of wine would be got out of the fridge during the meeting and chit chat. It was a very different kind of setup.

I think they're much more aware, first of all, because they're always late to the party. I went around the book fair, whatever the year that the volcano went off. Remember that one?

Joanna: Eyjafjallajökull, whatever.

Dave: Yes. So suddenly they had to talk to authors because all the publishers weren't turning up from abroad.

I went around with an iPad, and I was showing them Mirabilis on the iPad and saying, “You see, you'd have apps,” which they didn't really understand, “and you could have a publishing, effectively, portal and let people know the series they're interested in. It would tell them there's a new book coming, and they could go for extra info.”

I remember the publishers looking at me and saying, “It is not our business to have a direct relationship with our customers. That is for booksellers.”

Two or three years later, they were saying the future of publishing is to have a direct relationship. So you think, good Lord, you're always late with these things.

I mean, they're aware of that now, but it probably makes it harder for authors, as I say, to get established, but they're always going to need good ideas and that. I've been at many of those publishing meetings where they create their own ideas in house, and it's a rather deadening process.

Any committee creating stuff like that's always going to be horrible, so they definitely need people to just come in.

Usually what makes an IP interesting is the uniqueness of that person's mind, right? The rough edges that a committee would file off.

So I think sticking to your guns would be the major takeaway now. Believe you've got something that the publisher won't bring to it.

Joanna: Yes, which comes back to creative confidence again.

Dave: Yes, absolutely.

Joanna: What about marketing?

I feel like maybe again, back in the 90s, it was like, oh, you don't need to do any of that. But now that's changed.

Dave: I'm terrible at marketing, but luckily, I've never really had to do it because, as I say, owning all my own stuff, all I had to do was write to the publishers, invoking the clause that says it's out of print, I get it back. Then I can sell to 20 different publishers around the world on my own terms.

Again, AI is useful because, knowing I'm bad at publishing, I do occasionally ask the AI to advise me. It's much smarter than I am about “Oh, here's how you do a YouTube channel, and you've got to consider all these platforms,” that I've never even heard of, and it gives me links to them.

So I'm sure, again, I don't need to tell, I'm really of a generation that didn't know anything about that. So I mean, you know much more about it, I'm sure. People coming in right now will be fully up to speed with at least how to reach a wider market.

Joanna: Not that many people want to.

Dave: I mean, I was always of the opinion that I just like doing the creative stuff. I had publishers, game publishers or book publishers, who dealt with all the tedious bits. I mean, I'd have to go to meetings, but my job was to go there and be passionate about the ideas, not to explain it with a PowerPoint presentation.

So I kind of feel sorry for—well, unless people like marketing, there is always that problem that if all you are is very creative in writing terms, let's say, or art, and you're not good at marketing, there's a risk that some really great stuff will get missed because you don't know how to put it across.

Once we get the agentic AI, I hope it will clone me and go and do all the marketing on my behalf, with my face and my voice.

Joanna: Well, you can pretty much do that already, and that then becomes the question. I was literally looking at this the other day. I have a voice clone, even when I saw you a few weeks ago, it hadn't happened. I now have a voice clone that's done my latest audiobook, Death Valley.

I've said for years, when I get a voice clone, I'm going to license it. I'm going to make an income stream from people using my voice. I didn't realize what would happen when I actually heard it. Now I've heard it, I'm like, I can't possibly license it because it's way too me. So this is really interesting.

Faced with AI Dave, I wonder how you might feel about it doing a YouTube channel for you, or whether you think you might change your mind a bit like I did?

Dave: You see, I might. I look at a lot of old blog posts, and I think, now, of course, I couldn't just read them out as a script, because they're for the eye, not for the ear. But then, of course, I could say to the AI, “Take that blog post. Make it more chatty, conversational. Do it in my voice. Make a YouTube video.”

It's all my work, it's just slightly changed some of the text to make it work better for speech. I think I might. I don't know, would I find it weird? Maybe I'd have to get another voice. I think of it as my assistant, I don't think of it as “mirror, mirror on the wall.”

Occasionally I notice it remembers something I've told it. It'll say, you know, updating memory. Then I crack into that, and I think it's strange what it's chosen to remember of the things I've spoken to it about.

Joanna: It is very interesting. Although it's interesting because, again, we say, oh, we'll have a clone. We'll have a Dave clone or a Jo clone.

I don't want a clone. I want something that is a lot better than me at marketing.

Dave: Well, I'm sure it'll be better than us. I mean, our last refuge may be the actual writing, because it won't have had human—well, I say it won't have had human experience, but that's the curious thing about the degree of grounding that it's getting just reading everything.

I mean, clearly it has got—I've got to be careful how I put it because of the consciousness claims—but it's got a model of the world embedded in its language systems.

So, I mean, I would certainly use it to write a sympathy note to a friend. I'm terrible at things like sympathy notes because I only deal with problems by trying to solve them.

I don't deal with problems by emoting with people because I always think, where's the solution? Just telling you I feel bad because you feel bad, I haven't added anything. That's my neuro atypical way of thinking, I guess.

I think the AI is perfectly happy to be just there for you. So it would be the touchy feely version of me, I guess. Better at the emotional side.

Joanna: Which in itself is weird, right? People would say, “Oh, that voice is robotic,” meaning it has less feeling in it. Now, there are plenty of people who are robotic, or plenty of people who are not that interested in emotions.

It's actually funny, one of my first-use cases was with some of my writing, it was—

“Okay, take this and make it more emotional.”

Dave: Yes, exactly, and sometimes because you're just feeling a bit tired. Like doing a blurb, I say, look, I kind of want to do the blurb, but wow, I've just finished the 750,000 words of the book, and there's a lot of stuff. You think, well, where do I start? I don't want to summarize everything.

So I say, “Give me a really exciting blurb in the style of Robert E Howard,” or something. It's way over the top, but it makes me think, okay, those are the bits it's picked out are as exciting. So I can work from there.

Actually thinking about it, wasn't there that movie more than 10 years ago now, the Spike Jones one, Her, where they've actually got an AI writing greetings cards and sympathy cards. So already, in that future, they imagined a future where the AI was better at that than people.

Joanna: Yes, and the people, I think, who object to that, are the people who already write emotional stuff really well.

One of the reasons I don't write romance is because, you know, that's not me. People are like, “Oh, but you must think that,” and I'm like, no, I literally don't think that.

Dave: Yes, definitely. While I was doing the VulcanVerse books, there was a bit where I had—it's a long story, but you can end up at Troy. I wanted the possibility, kind of in backstory, just hinted at, that Achilles, who'd never had a proper life, you know, he'd come there as a very young man, might be falling in love with you, as the main character.

I didn't want to make it overt, so I said to the AI, “What tiny subtextual hints might indicate that I could work into the conversation?” Then it went through all the lists. “These are the things humans do when they're hinting or when they're trying not to indicate they're falling in love with somebody.”

I thought, wow, I'm actually asking the machine, but it was very handy. Sometimes with just the 10 bullet pointed lists, you think, yes, okay, those are all good points.

Joanna: Yes, completely. I agree with that. So you've mentioned, what have you mentioned? Chat GPT. You've mentioned Claude. You've mentioned Google NotebookLM.

Are there any other tools that you use a lot?

Dave: I use DeepSeek quite a bit. I've been using Gemini. They released the 2.5. I have to say, it's probably great for coding and maths, which is their real interest. I find it's pretty bad for writing.

I'll ask it for something, and it looks like it's paid by the word because it just gives you the longest way around and in quite horrible prose. Whereas I quite like the chattiness, the easy conversation you can have with Claude, or Chat GPT is good at that.

Yesterday, it started spitting out a load of things with some adjectives in Nepali and Japanese and Russian. I had to say, wait a minute, what? I don't speak this number of languages. What are you talking about? They go, “Oh, sorry. I'm probably getting mixed up in my training data.” So I'm a bit down on Gemini at the moment, but I use all the others.

Sometimes I'll set them on each other. I'll say, “Claude's just given me this, but I think there's probably some deeper insights. You'll notice them.” I'll tell Chat GPT. Of course, having been told that, it thinks I'm a very perceptive critic, and it role plays that.

So I always say to my wife, “Roz, you have to say please and thank you, for your own sake, to stay in the right mindset.” Don't treat it like just a Google search because when you talk to it in a certain way, you're getting it to lean towards a particular kind of response.

So saying at the start, “You are a really good book doctor, and you're about to tell me the flaws in this plot line,” you're much more likely to get some good flaws than if you just throw it at it cold.

Joanna: Absolutely. Although I am finding the ChatGPT o3 model just kind of extraordinary in that way, in that—

It will give me so much more than even I had thought to ask for.

Dave: I used to find when I first started working with teams on games—so I'd written for five or six years solo. You know, you're alone with your blank page. Then working on teams of people, where even though I was the lead designer, there'd be other people who I'd have to trust to do bits of the story or the design of the game.

You get to a point where you've got them to understand the ethic of it, what you're trying to do with the game, to such an extent that they will come up with stuff before you've even had to think about it. So working with teams is fun like that, and working with AI will be fun.

I had a horrible OCR scan of something I'd written 30 years ago, and it was totally garbled with percentages and question marks. The OCR just couldn't make sense of the text.

So I gave it to Claude and said, “I need this cleaned up. It's full of these artifacts. If I spend the afternoon on it, I can do it, but that's what you are supposed to do. So don't change anything, just write it as the original document without all the crap in it.”

So it took that, but when it came back it said, “I noticed that it was a scenario for this role playing game, and so I've also formatted all of the stat blocks for the NPCs using the standard notation from that role play game.” That's fantastic. I didn't even have to ask it for that, it was just bonus content.

Joanna: That is amazing. I think what's interesting, when you and I have talked about this before —

We're just not threatened by something like this.

I feel like o3 has been another jump in my perception of the whole thing. It’s that I'm not threatened that it's smarter than me, or comes up with things that I find interesting and take into other things.

I just don't feel that because there's always been people who are smarter than me. There's always people who are stronger than me, and know more than me, and all of this. So is that part of also feeling comfortable? You were working in a collaborative team, far more than most authors would do. So you're used to other minds, I guess.

Dave: Yes. I mean, it's not a new experience that there's another mind in the room that's smarter than I am.

Somebody said to me the other day, kids born today will never have known a world in which you can't talk to machines. I guess they'll just grow up expecting it.

I think the other thing is, every criticism that people level is just going to go out of date almost before they finished saying it, because it's such a quickly evolving field.

There's this kind of absolute zero reinforcement training that they're talking about now, where the large language models will create their own content and judge their own data. More than that, that they'll create their own problems and assess their own response.

They can find the very edge of their ability so as to push themselves an extra couple of percent, and then you just leave them running because they don't need a human being anymore. They found that's working. They expected it to work for things like code, but it's also working for natural, ordinary language.

So I think we'll just get an exponential increase in those fields now. So like you say, the genie is out of the bottle, so there's no point in having people writing papyri about how genies are bad for the economy of Baghdad or whatever. They're there, so you've got to figure out how to get the good wishes out of them, not the bad ones.

Joanna: Yes, and I heard somebody use the term “the original sin” of training on copyright data, in the way that at some point something was done that a lot of people don't agree with. Whether or not it ends up being legal or whatever, that may go on for decades.

We're so way past that moment, that anyone who says, “Oh, well, once that court case is decided, all of this will go away.” I mean, you mentioned DeepSeek, actually, which is the Chinese model. I mean—

Even if all the American models disappear, that's not the end of it, is it?

Dave: No. I know people don't like this analogy, but they don't like it not for the logical reason they say they don't like it, which is when I was a kid and I used to read comics, then I would think, I'll try drawing a hand like this artist does, or I see how he does faces. You'd study the style.

When I started writing—you know, thank goodness I've shaken it off—but I would try the style of HP Lovecraft, or whatever. I'd try those things out because that's how we learn. Then we gradually form our own styles.

So I don't think we should have one rule for us and one for the AI. Now, people will then say, “Oh, it doesn't learn the same way we do.” Well, it's training. It's learning patterns. We don't just learn patterns from public domain writing. Otherwise, all our writing would sound like we were Victorians. So it seems crazy.

If they aren't allowed to use anyone else's stuff —

They can have all of my stuff and train on it, because I want to be part of it. You know, in 2000 years’ time, some tiny, tiny little drop in this massive ocean of training will still be something that we wrote.

Joanna: I totally agree. I'm uploading all my stuff all the times to all of the LMs. I want them to know me. Also, with book recommendations and shopping coming to generative AI, you want your stuff to be there so people can find it.

Last question because we're almost out of time. So, obviously we had a bit of a laugh about Neurolink, but you're a game guy, and even if you say they're glasses, or VR, AR, like—

What are you excited about seeing in gaming and fiction worlds coming up in the next decade or so?

Dave: Oh, well, in gaming, I mean, I was thinking how about 15 years ago, I was working on a game for Microsoft, and it was like The Sims. We had thousands of lines of dialogue that were based on simple emotional and relationship states. So they were being accessed, and the characters would walk around.

If you weren't doing anything else, they would have these conversations. Some of the developers would come over to the coders, and say, “What level of AI are you using? Because I just listened to a conversation about going to the hairdresser, and it was really good.”

I said, there's literally no AI. It's just the emotional states and the relationships are calling from a massive bank of data. We're very good, as humans, at imagining there's some intelligence behind it, but now there can be. That's going to make, for example, NPCs in massively multiplayer games much richer.

There's always been this tendency to think of them as kind of monsters or to pre-script chunks of story, you know, the cut scene moments in a game. Those can be very good, things like The Last of Us or Thaumaturgy have got great writing, but they're really doing old writing. It's like movie writing, but in little chunks.

As I said before, I like the idea of stories as atomic level. Stories that are a cascade of events, I call it. Where stories emerge one step at a time, and the AI can do that. It can become the storyteller in real time. So I think that's going to completely transform massively multiplayer game.

You won't even know if the character you're talking to is a person or an AI, and so it means it's a complete world full of intelligences, as it were.

Joanna: Which is why some people say we're living in the simulation, right?

Dave: I heard a good argument by Yann LeCun the other day about why he didn't think we were in a simulation, but I can't remember the argument.

Joanna: It was so convincing!

Dave: Well, you know, it's, “I think I just wouldn't build it this way,” was pretty much the main argument.

Joanna: Whereas I think it doesn't matter.

Dave: It doesn't matter. No, it's like the zombie argument. Like, how do we know about consciousness? What if you had a philosophical zombie? And I go, well, we have no way of knowing what is going on in anyone else's head. You only know what's inside your own.

What difference does it make? They behave as if they're intelligent, that's all you require.

Joanna: Exactly. Oh, well, look, this has been a super fun conversation.

Where can people find you and everything you do online?

Dave: Oh, wow. Okay, well, I've got a Patreon that's called Jewel Spider. Jewel and spider, all one word, which is a kind of role playing thing. It picks up from Dragon Warriors 40 years ago. The artwork is by my godson, who's the son of the guy who did the original artwork. So it's no AI there, that's all human art.

I've got a blog, which is on blogspot, believe it or not. FabledLands.blogspot.com. On Substack I've got a thing called Hallucinations and Confabulations, which originally started as a writing-type Substack, but increasingly starts talking about AI.

Later in the year, I've got that Cthulhu thing coming out, which is whispers-beyond.space. It's kind of Cthulhu 2050. So again, it gave me the opportunity to imagine what the world of 2050 will be like, and how AI and robotics will have shaped it.

I'm on Bluesky as well. I'm still on Twitter, but I'm kind of hoping that somebody else will buy it at this point.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Dave. That was great.

Dave: Thank you, Jo. Great being on here.

The post Crafting Story Worlds, Creative Control, And Leveraging AI Tools With Dave Morris first appeared on The Creative Penn.